Abbie Kiefer Had to Figure out Why Television Was Important to a Book About Grief and Hope

Writing = Making and Solving Problems, Try This at Home

Hi Friends,

I’ve been in Portland over UBC’s reading week (a sort of early spring break) keeping my dad company through pre-transplant chemo, transplant, and the first days post-transplant, waiting for the donor cells to replicate and make a new immune system (and to see how his body will respond). We’re still in the waiting days.

Writing = Making and Solving Problems

Over time, I’ve come to realize that problems aren’t an impediment to writing. Problems are the substance of writing: we set problems for ourselves and we work them out. In this feature, I ask writers to dig into a specific writing problem and how they resolved it.

Abbie Kiefer is the first writer I’ve spoken with for this series who got in touch as an Okay, But How? reader to see if I’d be interested in a conversation about giving yourself assignments as a way to move forward with an emotionally difficult project. I was interested!

But I was also in the thick of dealing with my dad’s leukemia diagnosis and care, so I have to admit that I took several months to respond (which just makes me want to remind all of us, including me, that 1) if someone doesn’t reply right away, they might still be interested, and 2) even if we’ve taken forever to respond and it feels awkward, a response is often still welcome). I also appreciated how Abbie gave me a heads-up that the book dealt with a parent’s cancer and death, so I could make sure I was in a space to engage with it.

Certain Shelter is a beautiful book, and I’m so grateful to have had the chance to read it and share this conversation with you.

What are three key things to know about this book?

Certain Shelter is about making a life amid loss—poems that contend with the death of a parent and a fading hometown and the ways we can find or make shelter for ourselves in a sometimes-faltering world. So it’s a grief-steeped collection but it’s also reaching toward hope. Mary Ardery put it this way in a recent review: “There’s a lived-in quality to the book that seems to say: This is life—not perfect, but full.”

This book leans into regional identity. I grew up in Maine and the particulars of that place show up often—in poems about Yankee thrift and potato farming and the minor league ballpark in Portland. This isn’t to say that the book won’t speak to readers from other places, but if you’re a New Englander, you might feel an added connection to it.

Prose poems show up pretty often in the collection and I like to use narrative in my work—so if you enjoy fiction, this book might appeal to you, even if you’re iffy on poetry.

What’s a problem—small or large—that you encountered while making this book?

At the center of this book are my mom’s illness and death—a process of loss that made me easily distracted. I couldn’t write or read, so I stuck to what I thought of as easy television—cooking shows, predictable dramas. But even those became lenses for my grief, so when I started writing again, an ekphrastic1 TV poem found its way into what I was doing. And then I wrote a second one. And then, as I was shaping the manuscript, I realized that including two poems about TV shows seemed more than quirky but less than intentional. If I was going to use these two poems, I needed additional pieces to go with them to make the series feel deliberate.

What did you do? How did you move forward?

First, I had to figure out why television was important to this book about grief and hope. By writing about shows I’d watched as a kid, I was reflecting on nostalgia, which is closely related to grief. And I was showing how TV might shape our thinking about grief in general, like in this poem about The Wonder Years. I recently did an interview on Keep the Channel Open and host Mike Sakasegawa said he thought TV was important to the book because watching a show is a communal experience. I hadn’t articulated that for myself but he’s right. So that’s part of it, too.

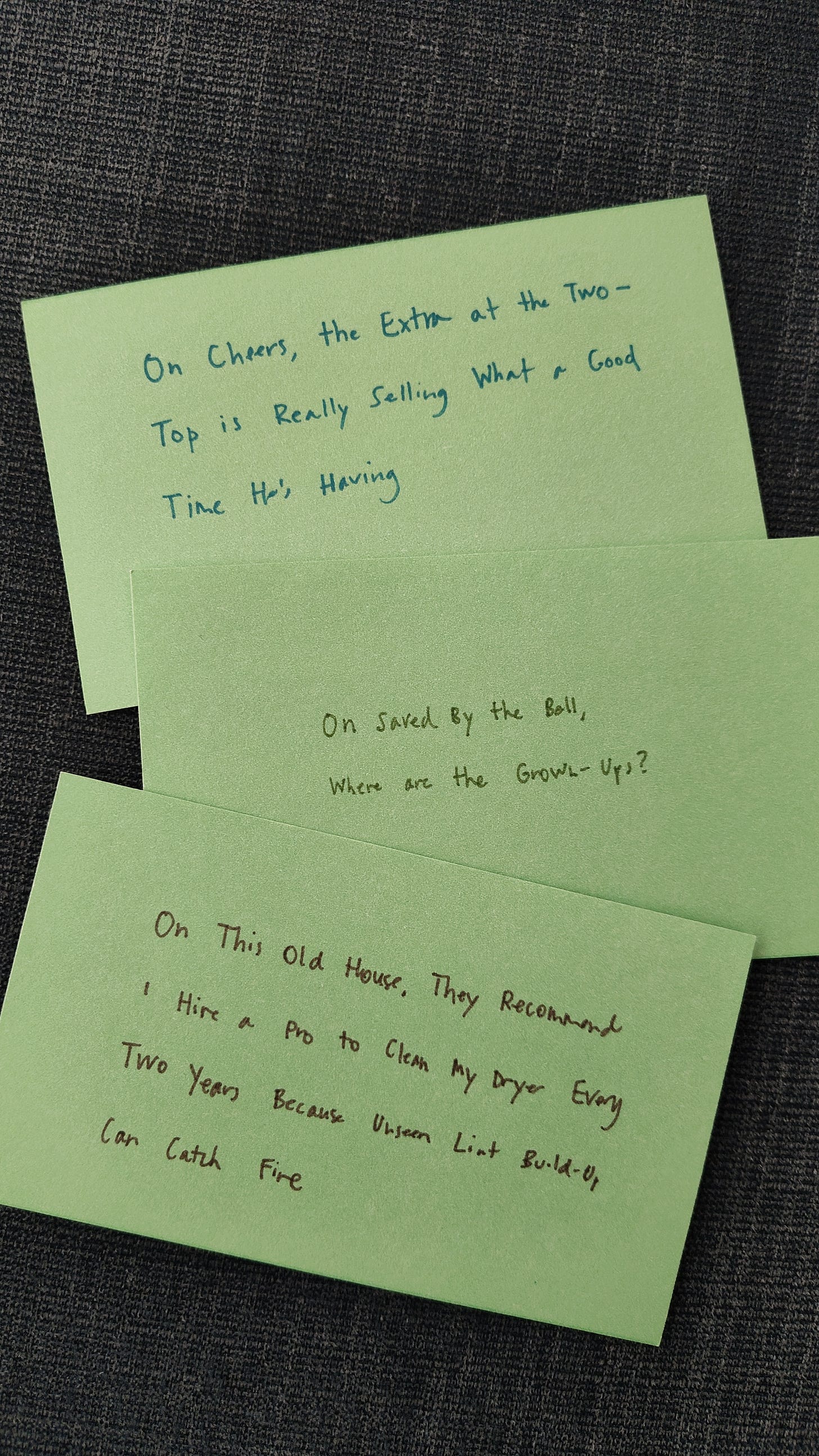

Once I had a rationale for writing these ekphrastic pop-culture poems, I had to start making them, and I approached this first by brainstorming a ton of possible titles, all constructed in the same way to reinforce the connection among them. My formula was to name a specific show and something specific that happened on it, like, “On Saved by the Bell, Slater Won’t Quit Calling Jessie Mama.” (I never actually wrote this one but I’m going to pick it back up again ASAP.)

Then I needed to find a way to connect what I’d seen in the episode to one of the book’s themes—grief, for sure, but ideas about belonging and identity and the value of work are part of the collection as well. I accepted that I wasn’t going to bring every draft to completion and that even a well-made poem might not have a place in the book, so I wrote far more pieces than I could reasonably include. The extravagance of that freed me up to try weird things and go in lots of different directions and feel less pressure about the whole process. In the end, I chose nine for the book, including, "On Antiques Roadshow, A Quilt Might Bring $600 at Auction" and "On The Joy of Painting, at 3 a.m., Bob Ross Promises Anyone Can Do This." But I liked the project so much, I didn’t stop—I wrote four more for a new manuscript I’m putting together. Plus that Saved by the Bell one, though that could expand too. Jessie Spano sonnet crown?

Abbie Kiefer is the author of Certain Shelter (June Road Press, 2024) and the chapbook Brief Histories (Whittle Micro-press, 2024). Her work is forthcoming or has appeared in The Common, Copper Nickel, Gulf Coast, Pleiades, Ploughshares, Prairie Schooner, The Southern Review, and other places. She is a poetry editor for The Adroit Journal and lives in New Hampshire. Find her online at abbiekieferpoet.com.

Try This at Home

Especially when writing is hard, remember that anything can become a source. Abbie turned to comfort TV when grief made it hard to sustain attention on reading or writing. And she found surprising scope for poems in the seemingly silly details of these shows. As a reader of Certain Shelter, I would also say that these poems allowed her to address grief and loss from unexpected and oblique angles that brought texture and surprise to the collection. How might a current videogame fixation, fast food order, pop song, or beading hobby offer material or a defamiliarizing lens for your current project? Start simply noticing and describing. See what associations and connections emerge.

Create a generative exercise for yourself. When Abbie realized that the TV poems she’d stumbled into had a place in her work, she designed a generative exercise for making more of them, a set of loose constraints to follow. She would start from a specific incident or observation in a particular show that, for whatever reason, caught her attention. Then she would follow her associations, making connections with her own experiences and emotions. I often ask MFA students working on a thesis with me to see if they can identify any poems or essays they might “make cousins for.” Can you identify a method or develop a loose “recipe” in your current project you might use to iterate?

Make more than you can use. Abbie talks about how setting out to make a whole bunch of TV poems freed her up to “try weird things and go in lots of different directions and feel less pressure about the whole process.” That’s another great thing about iterating based on a generative exercise: you can get less precious and more playful.

More Like This

Warm best,

Bronwen

PS: If you liked this post, please hit the heart to let me know! You can also support this newsletter by subscribing, sharing, or commenting.

An ekphrastic poem is a poem that describes and responds to a work in another medium, traditionally painting, but potentially also dance, theater, or, as here, TV!

Sending love for the waiting days!!

As always love the ideas at the end for problem solving and idea generation!