Holly Flauto Got Tired of Filling in the Blanks with the "Right" Answer

Writing = Making and Solving Problems, Try This at Home, Let's Help a Writer for Free!

Hi Friends,

It is somehow already mid-October! I am in the thick of things, and I imagine you are as well. I hope you enjoy this conversation with Holly Flauto about how we might hijack the endless everyday genres of immigration forms, insurance documents, and permission slips by making them a space for art-making.

Writing = Making and Solving Problems

Over time, I’ve come to realize that problems aren’t an impediment to writing. Problems are the substance of writing: we set problems for ourselves and we work them out. In this feature, I ask writers to dig into a specific writing problem and how they resolved it.

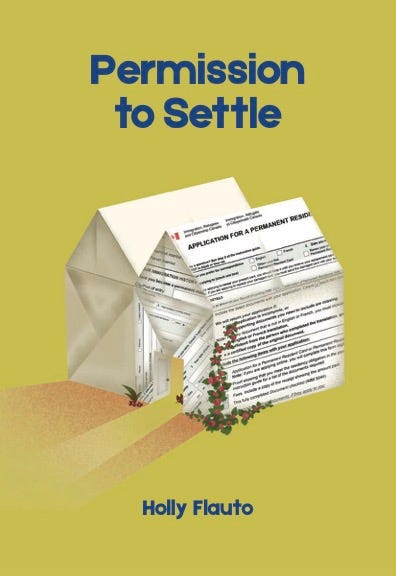

Holly Flauto’s Permission to Settle is just out this month with Anvil Press.

I know Holly from my friendly Friday afternoon writers’ meet-up, where we’ve discussed important things like font choices, grading approaches, hojicha lattes, American roots, and long poems. Holly’s new Permission to Settle might be one of these—Is it a book-length poem? A serial poem? A poetic sequence? In our interview, Holly talks about writing into immigration forms, learning traditional introductions, and the difficulty of excerpting a “project book.”

What are three key things to know about this book?

Each poem answers a blank in one of the immigration forms needed for permanent residency. And each one does that in its own form. This isn’t a book of sonnets or concrete poems or couplets or free-form. It’s all of the above. The result is that the form is both chaotic and structured, reflecting the immigration forms and process itself. The answers to the blanks on the immigration application have burst out of their normal official structures into poems—each one stretching out in a different way. I've been trying my hardest to coin a new poetic form to reflect the purposefulness of its structure in the seemingly unstructured or multi-structured presentation. Best I have so far is "bloated application response." I think I have some work to do.

It’s a book about learning. I’ve learned so much about what it means to be a more responsible settler on these lands in the eight years since I became a permanent resident, and then a citizen, and I look back at some of the poems and realize the naivete with which I approached allyship then—and acknowledge that I still do. That work is ongoing for me. A recent conversation with a Capilano University colleague Bobbi-Lee Copeland—about adding traditional introductions to my classes— helped me realize that the switch from filling in blanks with the “right” answer to substituting in a creative answer has become an attempt at a traditional introduction about me and who I come from. The first thought that comes to mind is “how serendipitous!” and then I think that it's really the universe at work bringing something forward for me in the way it’s supposed to be even though I didn’t understand it yet.

In each poem, I am trying to bring forward something deeper, usually about political structures, social structures, or family structures, but I also want the poems to be fun to read and joyful in their own way. At one level, this is a book of poems about my experiences. But I hope others see themselves too, and that my immigration story resonates beyond its reality.

What’s a problem—small or large—that you encountered while making this book?

One problem is that the poems don’t really come out of the whole book shell very well. The book in my mind is actually a long—very long!—140-page poem. Whenever I’ve tried to pull poems out for submissions or contests or readings, I feel like they lose context without their neighbors.

What did you do? How did you move forward?

I have read several of them at readings and events, and in some instances, I rewrote poems to make a “public reading” version.

Interestingly to me, none of these poems were published elsewhere before the book. I have that fear, thinking what if it’s because they aren’t very good, but then I tell myself that they found their perfect print home with Anvil all together in Permission to Settle. I got a note from my publisher, Brian, in the layout process that he was surprised it was clocking in at 140 pages and wondering if we should cut it down a bit. But then we kept it as it is. (I didn’t tell him that I have an additional 40 pages of poems based on a different form that I took out of the manuscript.)

There were other times in the editing process when I had to ask myself why I made this so complicated. Did “Issue X” really need to fit with the forms or was ok to evoke creative license? The table of contents was super tricky because the forms in the immigration process themselves don’t have parallel structures. Some have sub-sections and others don’t; some have additional forms to fill out depending on how you answer. I felt that the hierarchy of sections of poems needed to reflect that, but it didn’t fit well with the traditional table of contents. Staying true to the forms often won out once I remembered that this complication was part of the bureaucracy and anxiety of the experience I wanted to convey.

Holly Flauto(she/they) is a poet, story-teller, learner, and instructor living and writing on the traditional, ancestral, and stolen territories of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm, Sḵwx̱wú7mesh, and Selilwitulh Nations. Her fiction and creative memoir have previously been published in The Ex-Puritan, Joyland, and The Rusty Toque. They also perform as Stella Palermo on the local story and poetry slam stages. Holly grew up moving between the US and South America; she immigrated to Canada in 2008. Holly teaches writing in the English department at Capilano University. You can find more of Holly’s work at www.hollyflauto.com or follow them on Instagram.

Try This at Home

The approach Holly takes here—writing poems into an official immigration document—is sometimes called a “hermit crab,” after the crustacean who slips into someone else’s discarded shell to make a portable home. Why not try one yourself? Pick a non-literary genre showing up in your life these days (dating app? PTA email? doctor’s office forms?) and use it to make a poem (or story, or personal essay, or something in between).1

Students working on book-length poems sometimes stress about trying to place selections in magazines. Holly’s example tells us: don’t panic if selections and excerpts don’t find homes or you don’t find it in yourself to slice and dice and submit. Some work emerges into the world fully formed as a book!

Even when poems have been published, we can choose to see our work as still open to change. When Holly talked about making “public reading” versions of some of her poems, I thought of Rachel Zucker’s interview with Ilya Kaminsky where Kaminsky says of public readings: “What I am interested in when I am reading a poem is trying to revise it again. I am an obsessive reviser, obsessive writer. . . . So I try to write it again by the voice, which I do with different tonalities, different syntax.”2 Consider: how might a public reading offer a chance to revise a poem, however slightly, through tone, pacing, context, or another variable.

Let’s Help a Writer

A great way to support a writer is to share their events with friends who might be interested. Holly has several exciting events coming up, including a Vancouver Writers Fest panel conversation that I’ll have the pleasure of moderating just one week from today. (I love moderating. I get to ask lots of questions!). This is a stellar lineup, and I’d love to see you there!

More Like This

And more!

Warm best,

Bronwen

PS: If you liked this post, please hit the heart to let me know! You can also support this newsletter by subscribing, sharing, or commenting.

My friend Austen and I have started referring to all medical intake forms as “hermit crab essays,” as in, “I still need to finish the hermit crab essay for my physical therapy appoinment.”

This whole interview is so great! Give it a listen!

Footnote 1 of this post is hilarious! Hermit crab essays are everywhere! So are poems :)

Public readings as a way to revise -- love.