A Writer's Commonplace Book as "Transitive Diary"

Life swerves, ordinary rituals, and sustaining technologies with company from Jillian Hess and Amer Latif

Hi Friends,

Two weeks ago my life took a turn.

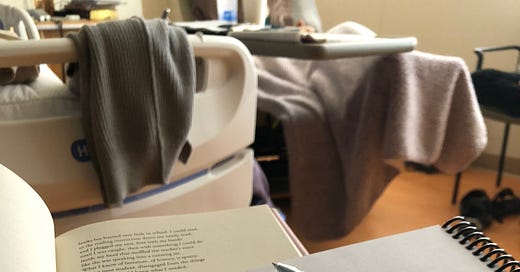

On the morning of June 18th, I got an email from the president of UBC confirming my promotion to Associate Professor of Teaching with tenure effective July 1st, 2024. Then that same evening I got a text from my sister saying that my dad had gone to the ER with pain and shortness of breath and then a text from my mom saying that he’d been diagnosed with leukemia. I flew to Portland a few days later, and I’ve been in the oncology ward with its strange fast/slow, full/empty days of chemo drip, every-four-hours vitals, and blood transfusions every other day. If you know my dad, you know he’s a runner, always in motion, bristling with energy, getting home from a work trip and immediately heading out to mow the church grounds with a tractor. So this is a dramatic change. And acute myeloid leukemia is a big uncertainty.

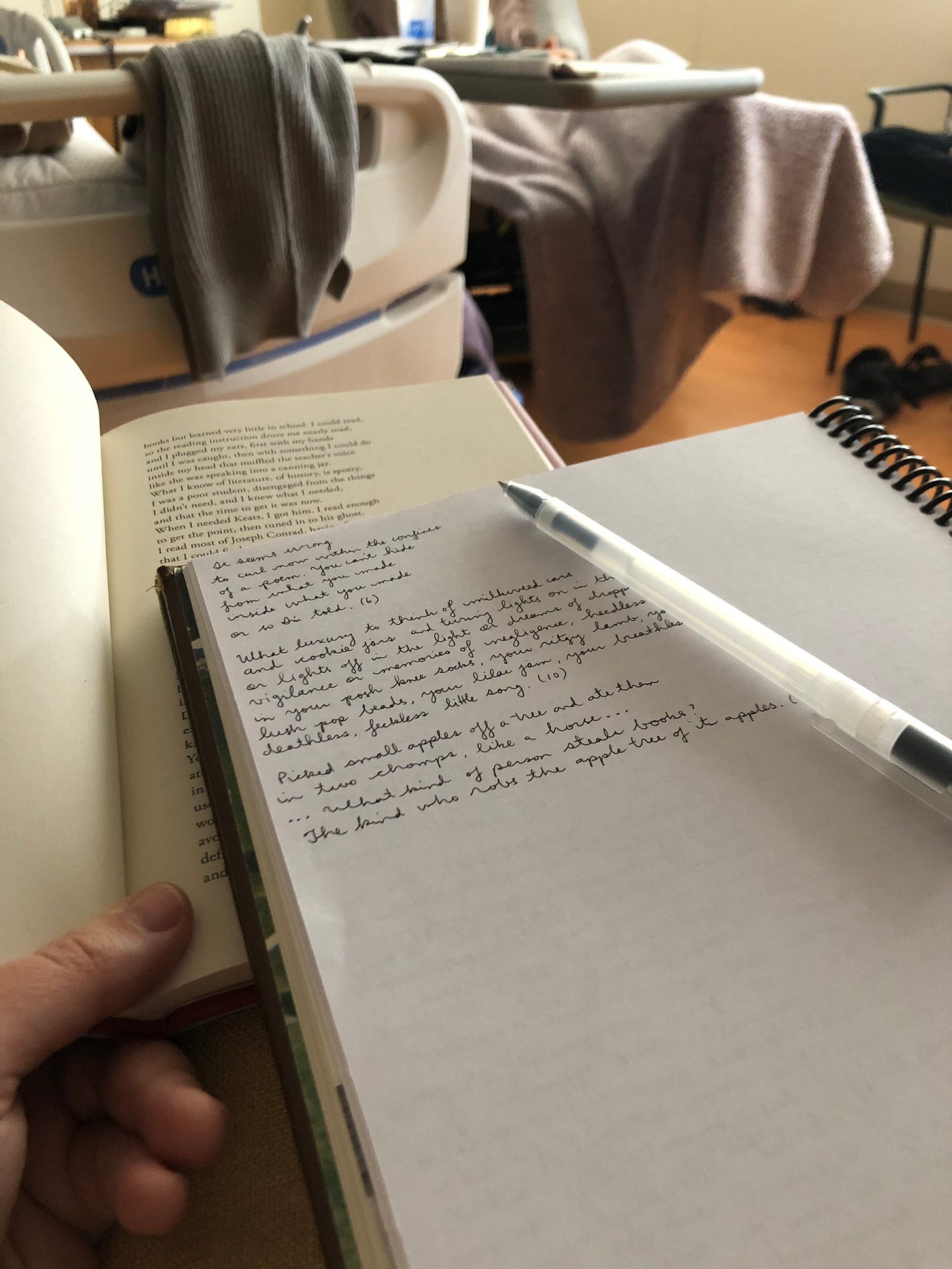

I’d been drafting a note for you about commonplace books—how I use them in my writing and my teaching. In brief, commonplace books are collections of quotations, often accompanied by reflections. I haven’t been able to write much in the hospital, but in moments when dad is napping I’ve brought out a notebook to copy passages from Diane Seuss’s Modern Poetry. So I decided to complete this note from where I’m writing now. The passages in Seuss’s poems that strike me this week are particular to this moment in my life. And that’s part of what interests me about keeping a commonplace book. It can be a form of study, but the way I use it often feels as much like a “transitive diary”: a diary that takes an object.

How I Came to a Commonplace Book Practice

I’ve been keeping a notebook regularly since I was twelve. At some point, I started copying quotes from my reading into my regular notebook.

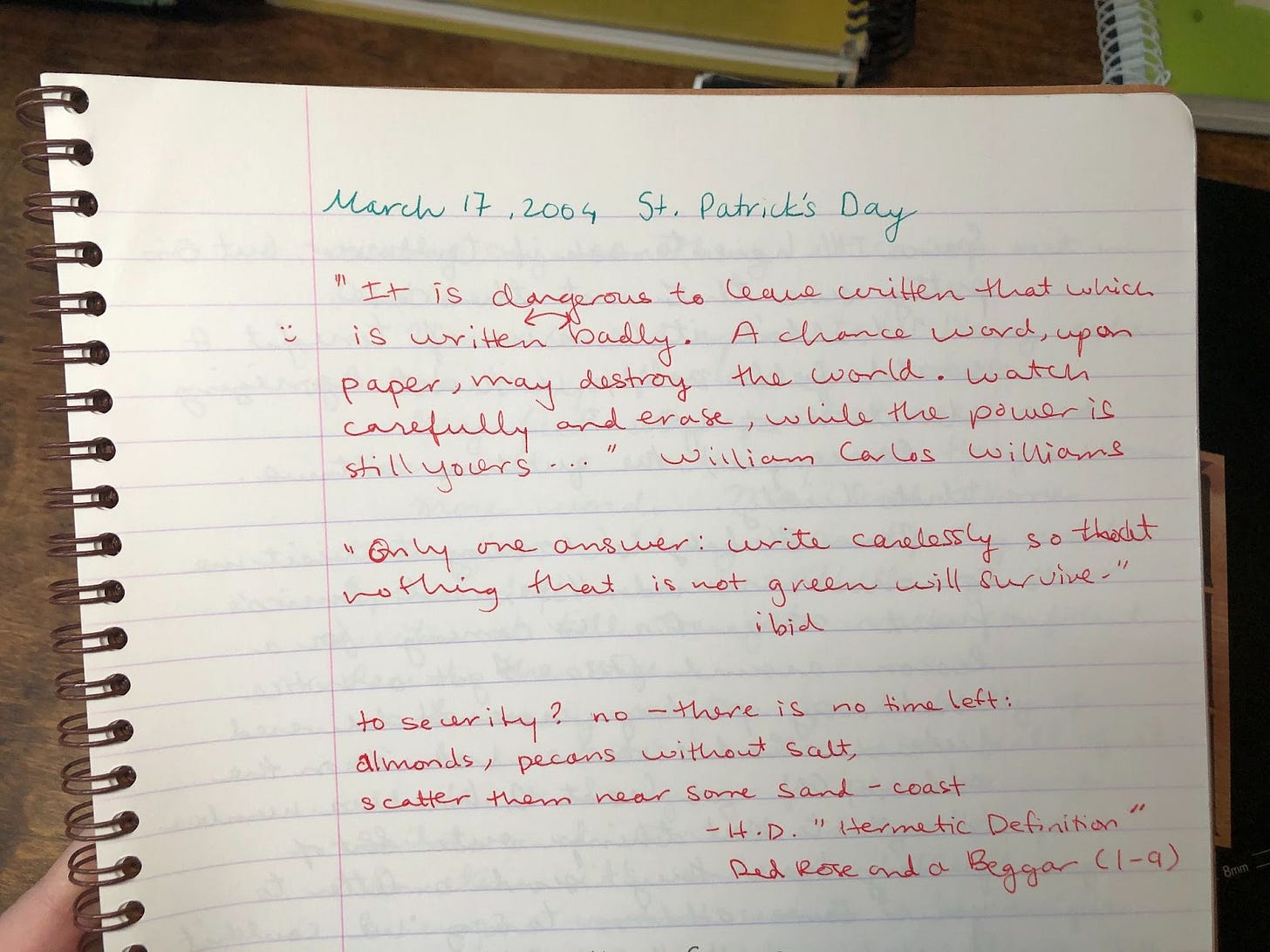

Here’s an a quote-keeping page where I wrote a smiley in the margin because I messed up WCW’s quote about the danger of leaving things “written badly badly written” In this notebook, all of the quotes from what I was reading are in red. In March, 2004, I was in Italy with a broken ankle waiting to hear back from MFA programs. I was reading Poems for the Millenium, an anthology I’d made space for in my suitcase to make sure I had access to English-language poems while teaching in Bologna. Instinctively, I wanted to hold onto bits of my reading that struck me.

Years later during my Ph.D., I was part of life-changing writing group (still going strong!) that included

, who was working on Romantic and Victorian commonplace books. I loved reading her chapters on Coleridge’s blurring of quotes with his own compositions and George Eliot’s deliberate epigraph gathering (and I’ve been so happy to see Jill’s work find enthusiastic readers first in her book How Romantics and Victorians Organized Information: Commonplace Books, Scrapbooks, and Albums, and more recently via her unmissable newsletter ).

What did I learn from Jill? The commonplace book is an old technology. As far back as Marcus Aurelius, writers have kept notebooks dedicated to gathering, organizing, and reflecting on quotes, examples, and ideas from others. Depending on their goals, writers have organized and approached their commonplace books in different ways. Some have been deeply concerned with data curation and indexing systems for tracking information, while others have moved fluidly between the passages by writers they're reading and their own drafts.

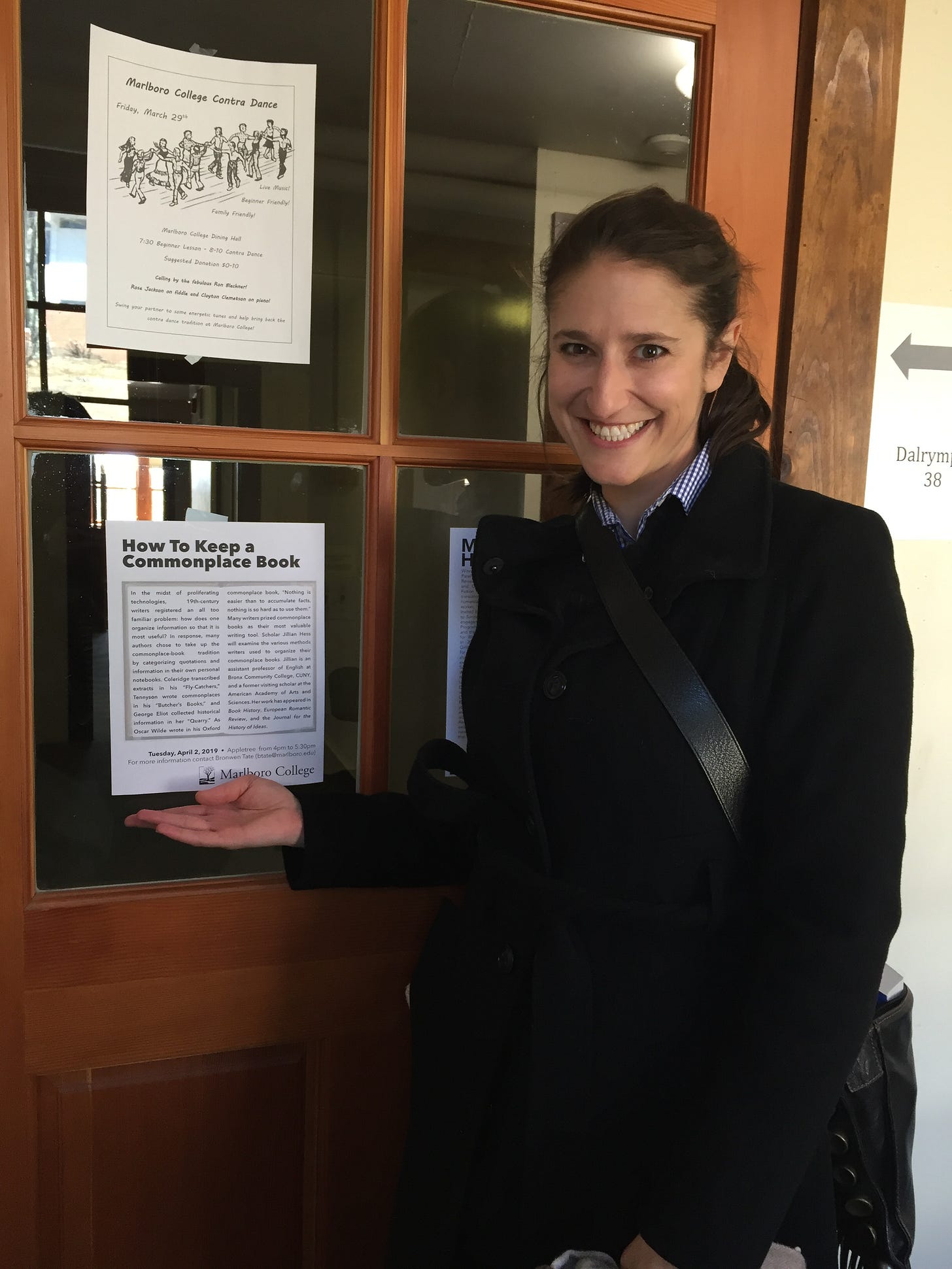

In my first assistant professor position at a small college in Vermont, I encountered the commonplace book not as an object of historical study, but as a tool for writing and teaching. In particular, my colleagues Amer Latif and Meg Mott used commonplace books to help student track and deepen their attention to constitutional politics or religious ritual over the course of a term. After conversations with them, I worked my way to a commonplace book practice of my own, which I’ve shared with students both at Marlboro and at UBC, where I teach now.

As a writer and writing teacher, here’s what I think a Commonplace Book practice can help us do:

develop a deep reading practice

pay sustained attention to form (the how of writing on the page)

clarify and extend our thinking by engaging with specific passages (from poems, interviews, essays, etc.), reflecting on why they inspire, puzzle, delight, or infuriate us

make connections between what we read and our own preoccupations and questions

Reading with a focus on how a poem or essay or story makes meaning is an essential part of growing as a writer. We learn what is possible—and what might be possible—from noticing what moves us, what frustrates us, what surprises us, and then taking the time to figure out how exactly each effect is achieved on the level of the transition sentence, poetic turn, metaphor, rhyme, or semicolon.

In selecting quotations to collect, we make choices about what matters to us and what we want to sit with.

In our reflections, we practice thinking on the page without a particular destination or outcome in mind. In this way, we open ourselves up for discovery.

How?

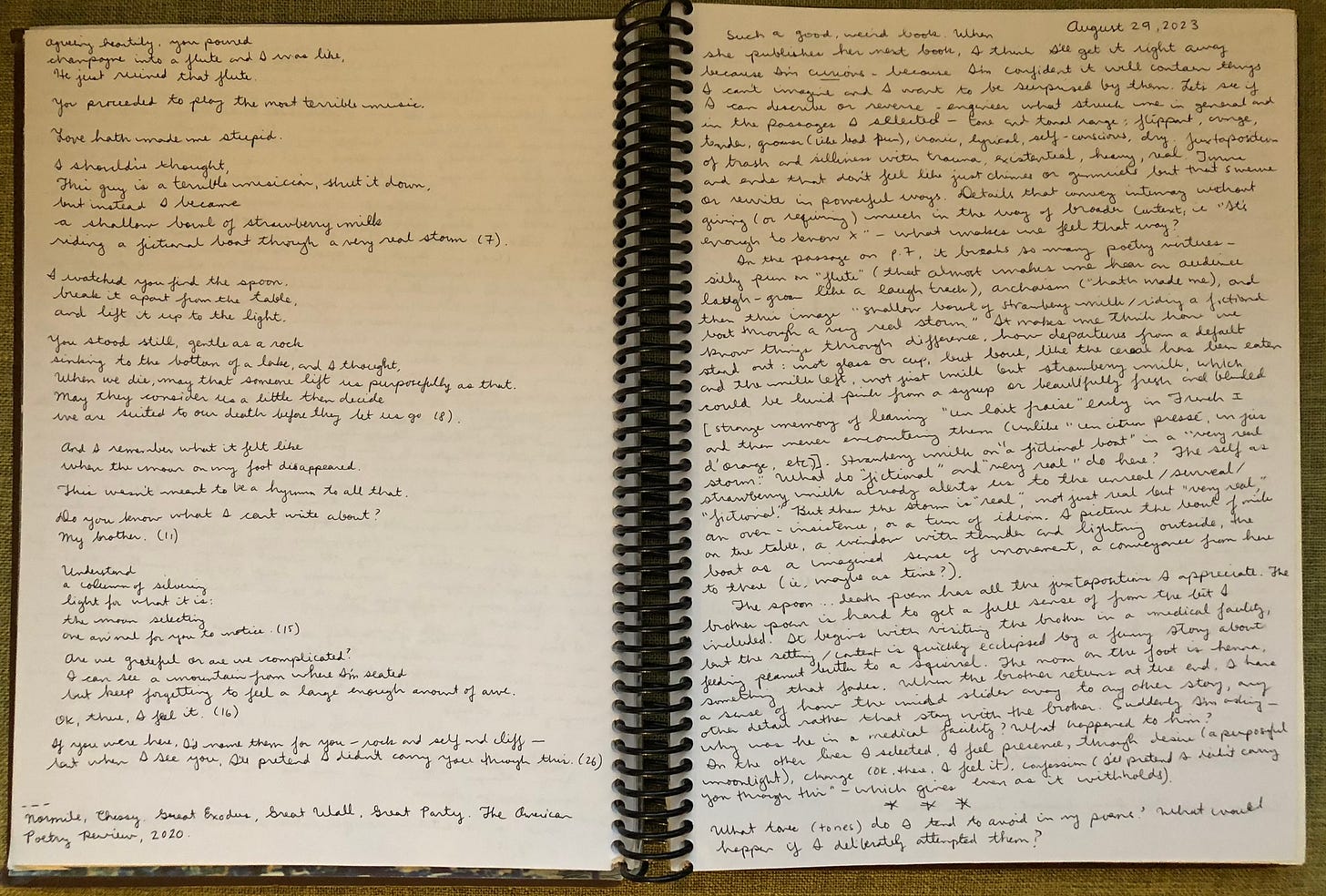

Here’s my approach to a commonplace book practice for creative writers. You need a notebook that can lie flat with two open pages. You decide what feels right regarding blank/lined/dot-grid, page size, choice of cover, bound or spiral, etc.

Each commonplace book entry:

might select lines and passages from an entire book, or

might focus on the first section of a book, or

might dig into a single essay or chapter, or

might gather selections from an interview, etc.

Each entry includes the following elements:

Left-Hand Page

A citation (at the top or bottom of the page where it's easy to find)

Quotations from the text. These can be full poems or paragraphs, single lines or phrases, or even a list of interesting verbs and the pages on which they occurred, or a list of words you looked up in the dictionary and their meanings. Whenever possible, include page numbers so that you can find these passages in context again when you want them!

Right-Hand Page

The Date.

Noticings, reflections, responses. What’s happening here? What caught your attention and why? What does it add up to? What’s making it work or not work? This category is pretty flexible. You might respond to an idea or you might concentrate on form. Push yourself to make connections between form—at any level—and meaning-making.

Questions for yourself / questions to discuss with others. What are you left wondering about? What do you want to get someone else’s thoughts on? What do you want to think more about?

Optional Extra for Right-hand Page

Things to try. What could you take from this text and incorporate into your own writing? What is this writer doing that you could try out yourself? "Things to try" could be as specific as “Try writing sentences with semi-colons that place concepts in relationship the way James Baldwin does” or as broad as “Write a coming-of-age narrative and, after a few pages, use Baldwin’s phrase ‘But I cannot leave it at that; there is more to it than that” as an impetus to dig deeper and wrestle with what you’re leaving out.”

Note on time: You can complete both pages in a single sitting, or you can copy down passages as you're reading, and then write your reflection and questions that following morning (or even weeks or months later). You might underline or flag possible passages to return to as you read, and then review them and pick the ones you want to copy at the end of the essay/book. Experiment with different options to see what works best for you.

Commonplace Book as Ritual

In my writing and in my teaching, I’ve found it helpful to approach the commonplace book as a ritual.

This ritual asks us to practice:

Picking specific lines, poems, or passages to sit with and hold onto (out of all the many possibilities).

Accepting the contingency of our attention: On a different day, we might pick different quotes, might write different reflections, or notice different things. That's fine.

Copying other peoples' words out by hand, which invites us to inhabit their uses of language differently than a quick copy+paste would do. When we make a mistake and have to cross something out, we have a chance to notice where the writer's destination diverges from our own expectations or defaults. This is interesting.

Being okay with our imperfections: messy handwriting, distracted mind, indecision about what to pick, and so on.

Focusing on details and paying close attention.

Writing as a vehicle for thinking.

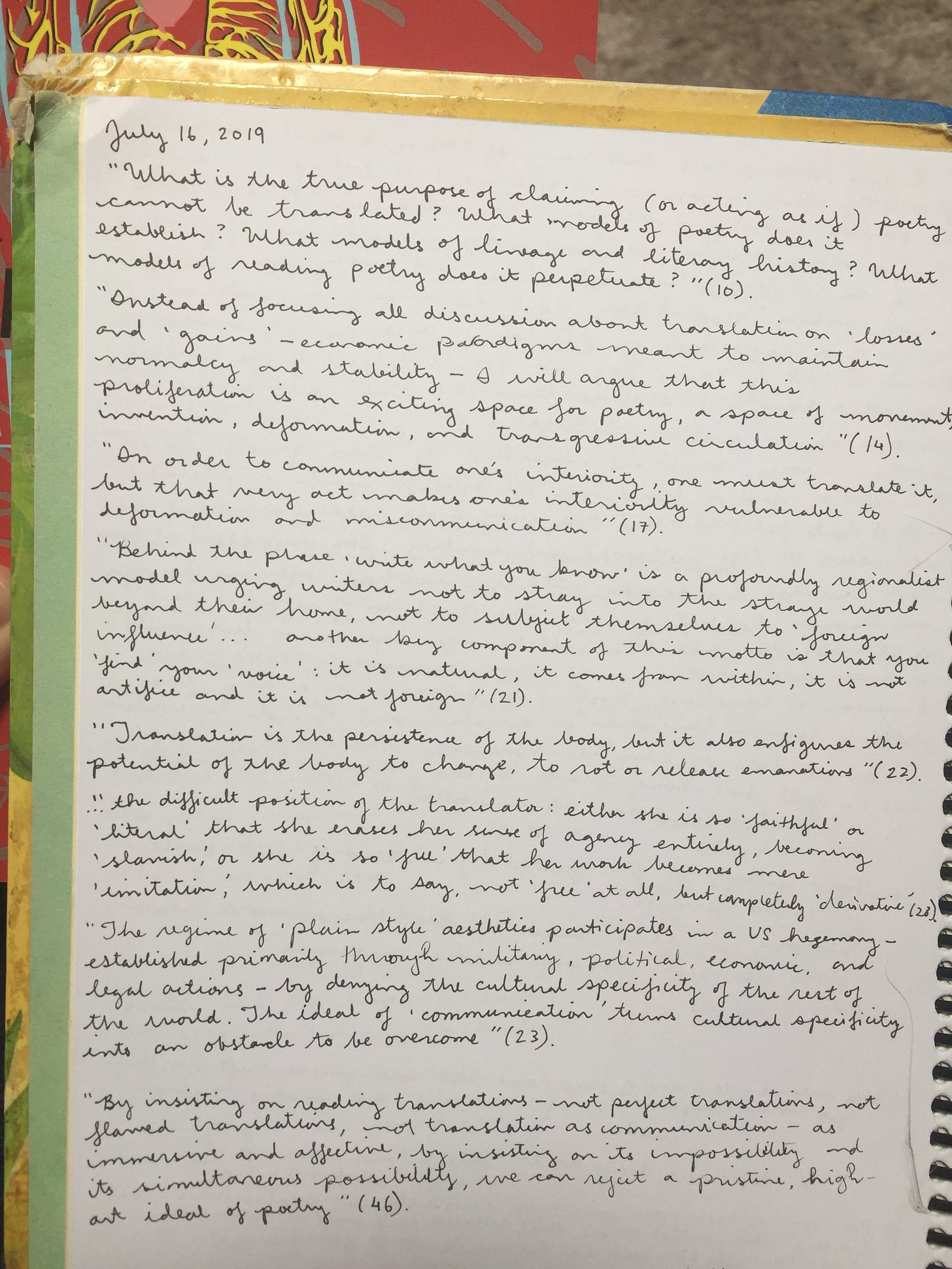

Commonplace book writing often feels to me like writing that has no set destination but is open to the possibility of arriving. I’ve found its arrivals to be various: many books I’ve assigned and writing exercises I’ve designed have started here, as have clarifying lines that became guiding talismans, an interest in translation’s questions in 2019 that became a translation workshop in 2024, ideas for essays, techniques for poems, passages I’ve pulled up to read out loud during student meetings and dinner parties. Others I know I’ve yet to discover.

As my friend Amer wrote for his students:

To take a note is to confront a foundational dilemma of living and to face the tragedy of human action. There is a part of us that seeks closure, that wants to know something inside out, that wants to “get” it. Then there is the part of us that recognizes too well that we never “get it.” There is no final arrival, only movement. As soon as we arrive at a point of understanding, new pathways open up. This world, both outside and within ourselves, is forever changing and in transit. Our understanding and our actions based on this knowledge are incomplete, partial, tentative, provisional, non-exhaustive, temporary, interim, impermanent…

Why not consider learning to be a process just like eating? We get hungry, we have an idea of what to make, we gather the material, make the food, and eat. Then we repeat it multiple times a day and never try to find a final or perfect solution to hunger. It is precisely this imperfect solution to an ongoing problem that becomes the occasion for creativity and joy.

Reading Amer’s words in this moment, I’m struck by his metaphors of hunger and food. Eating is hard for my dad right now. Food doesn’t taste good, and things he used to love turn to putty on his tongue. As I write, I’m sitting in my childhood kitchen simmering chili in hopes that the spice will be enough remain palatable, to offer a solution for tomorrow’s meal.

If I were writing a commonplace book entry on Amer’s notes today, I’d probably write about my dad’s changing relationship to hunger and pleasure in food. Can there still be creativity and joy here? It’s hard.

When I say that the commonplace book can be a “diary that takes an object,” I mean that it’s an invitation to write from wherever we are in a way that’s also moved, aerated, challenged, and solaced by the thinking of others. That’s something I need these days.

Yours,

Bronwen

PS: An interview I did a few weeks back for

’s recently appeared and you can read it here if you want.

Sorry to hear you’re going through this difficult time Bronwen. And also delighted to see Jillian featured here - I’m a big fan of commonplace notebooks and Jillian’s Notes is always so inspiring 🧡

so sorry to hear about your dad, Bronwen. I'll be thinking of you and your family. and thank you for sharing this guidance on keeping a commonplace book--I've been thinking about how to revise/re-energize my first year writing class for the fall, and that feels like one really useful way in.