Lois Eustis Tate Needed to Be More Forthcoming About Who She Was

Writing = Making and Solving Problems, Try This at Home! Let's Help a Writer for Free!

Hi Friends,

I’m heading into my last two lectures for the big class1, final grades, and all that end-of-term wrap-up. Students are making such exciting work! It’s bittersweet to end each term—a relief after the onslaught of the semester’s responsibilities, but also a farewell. Fortunately, former students keep showing up to the Whole Cloth Reading Series to say hello and take in some poetry. Today, I have a pretty special interview to share with you.

Writing = Making and Solving Problems

Over time, I’ve come to realize that problems aren’t an impediment to writing. Problems are the substance of writing: we set problems for ourselves and we work them out. In this feature, I ask writers to dig into a specific writing problem and how they resolved it.

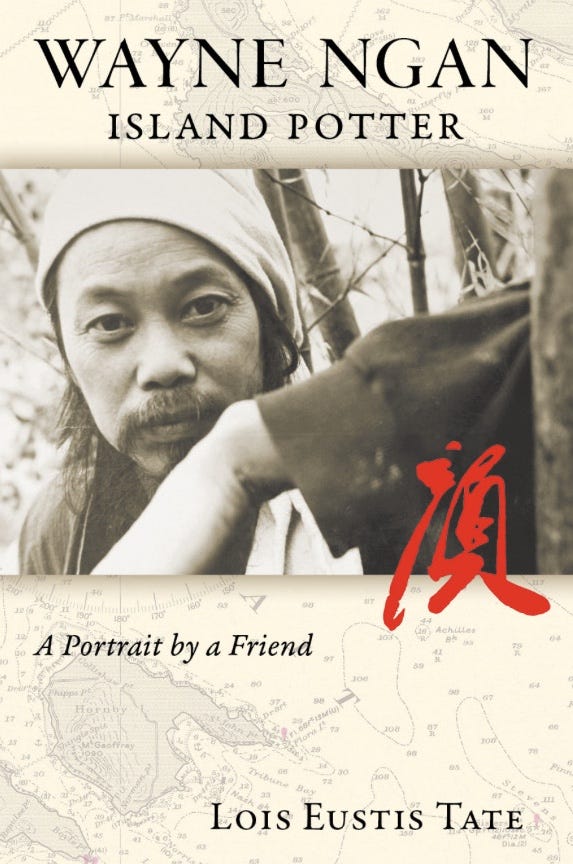

As you may have guessed from the name, this writer and I go way back. Yep, she’s my mom. And her book Wayne Ngan, Island Potter just came out!

Lois (aka Mom) started this project when I was a 23-year-old MFA student, so this book and I have grown up together over the past twenty years. At several points along the way, I had the pleasure of reading and offering thoughts—first on sections and later on versions of the entire project as it took shape. (a step towards reciprocity after all of the high school essays she’d proofread for me). We’ve also spent hours walking (in person or on the phone) and talking about how to structure the narrative of a life, the ethical responsibilities of writing about the complicated relationships of real people, or how to decide that you’re done with an ambitious project.

It’s deeply satisfying to see her years of labour manifest in this beautiful book, and I’m so pleased to share our conversation with you today.

What are three key things to know about this book?

It’s a hybrid—it runs on biography gas and memoir electricity; or do the metaphors work better the other way around? About two-thirds of the book about my lifelong friend, Wayne Ngan, is written in close third-person narrative POV. The other third, consisting of chapters and shorter sections written in first person, focuses on Wayne’s influence on me in my teens and twenties, and, in later years, how my research and process impacted his understanding of his family history.

Wayne was an artistic genius who became a renowned Canadian ceramicist. In the course of the story, a reader witnesses his ability to focus, one-pointedly, first of all, on the game of marbles in the schoolyard; secondly, on the game of baseball as a pitcher; and finally on the creation of art, which began under the tutelage of my father, his junior high art teacher. In witnessing his evolution as an artist, the reader sees the traits inherent in genius at play in Wayne’s life: obsession, perseverance, resiliency, curiosity, imagination. With charisma and a sense of humor thrown into the mix, Wayne was bound for professional success.

My father and Wayne had many things in common. Aside from an obsession with art, they had both experienced childhood trauma and found solace in their obsession with creativity. Both had difficult relationships with their fathers, and both suffered deeply from a rift in their relationship with one another. Part of my motivation in delving into Wayne’s story was my need to understand more about the impact of early trauma and the power of creativity to heal it.

What’s a problem—small or large—that you encountered while making this book?

I decided to write Wayne’s story at the age of sixty. Yes, I was the aging English teacher who decides to write a book. Most of my previous writing had been confined to journaling and academic writing, with the occasional poem emerging when I was in a mood. In 2005, I faced the steep hill of learning the art of creative nonfiction writing, while trying to wrestle Wayne’s complex story into some kind of structure that made sense—to me and hopefully to readers.

There was the difficulty of Wayne’s tangential way of recounting his experiences. We would start in his Chinese village and end up in his philosophy about centering pots. He’d been to China many times and confused one trip with another. He had always maintained that he arrived in Canada in 1951, the date his daughter put on his website. But when he dug out his immigration card, it was both stamped and hand dated: March 16, 1952. Every so often, Wayne would say: “Don’t remember that, you have to ask my brother. He’s older but has a better memory.” But the problem was that his brother lived in Guangzhou. Would I ever get there? How to organize all this?

Also, I knew this was a personal story. I had no interest in writing a traditional biography with an objective tone. I wanted to be truthful and base my narrative on fact as much as possible, but despite my background in art, I was not an expert in ceramics; someone else will have to write the book detailing the specifics of Wayne’s clay bodies and glazes. I wanted to focus on Wayne’s personality and lived experience. So the problem: how to structure this beast?

What did you do? How did you move forward?

I began by working on the level of the scene, learning those building blocks. I wrote scenes from Wayne’s point of view, based on events he described in detail, as I recorded our interview sessions. I wrote scenes based on my memories of times with Wayne, from my teen years, and then from the early 1970s when I moved to Hornby Island, where Wayne lived with his wife Anne and their first daughter. I wrote scenes based on my visit with Wayne and his brother in Guangzhou in 2012.

But eventually, I had to move from a focus on scenes to a consideration of the overall structure. The manuscript ballooned to 126K words, then shrank to 80K, as I hacked ruthlessly at my own sections, telling myself: “This is a story about Wayne—don’t ramble on about your own experiences.” But a helpful editor pointed out that, as a reliable narrator, I needed to be more forthcoming about who I was. As I added things back in, somehow new insights developed about my father and Wayne. I read about the relationship between trauma and creativity and contemplated the tragedy of the breakdown of relationships suffered by many victims of early trauma.

Eventually, the manuscript settled in the 90K range with two timelines running parallel. One, the timeline of my interviews with Wayne, started with the prologue recounting my visit to Hornby in 2006 and ended with a final chapter on my visit to Guangzhou in 2012. Timeline two recounts Wayne’s lived experience, beginning with his life as a peasant child in a village near Guangzhou, and ending with his death, in June 2020, in the Epilogue. It finally came together in a way I could call finished.

Now I can claim: I published my first book before turning eighty.

Lois Eustis Tate grew up in an artists’ home in Richmond, B.C. and graduated from UBC in 1968 with an education degree in Art and English. In 1980, she married an American and settled in Portland, OR, where they raised two daughters. After many years of teaching, Tate retired in 2012 and began delving more deeply into creative writing. She loves spending time with her five grandchildren and retreating on the Oregon coast with her husband of forty-four years. Lois can be found online at www.LoisEustisTate.com or on Instagram.

For more on Wayne Ngan and his art, check out Wayne Ngan Studio or follow Wayne Ngan Studio on Instagram. Wayne’s daughters Goya and Gailan welcome visitors to his Hornby Island studio each summer.

You can also sign up for Letters from Lois to get installments of her international 1970s hitchhiking adventures. 😁

Try This at Home

When faced with overwhelm at how to write this highly-researched account of a long and complex life, Lois says, “I began by working on the level of the scene, learning those building blocks.” While writers may feel an impulse to outline or structure a project, starting with scenes—without a particular structure or agenda—can allow you to discover a project’s key concerns through close attention to the moments, sensations, and conversations that embody them.

Lois mentions the realization that “as a reliable narrator, I needed to be more forthcoming about who I was.” Constructing a narrative persona is essential work for any creative nonfiction project. In my teaching and writing, I often return to Vivian Gornick’s The Situation and the Story (which Lois and I also discussed while she was working on this book). Gornick writes about the need to identify which self (of the many selves at our disposal) is speaking: “Out of the raw material of a writer’s own undisguised being a narrator is fashioned whose existence on the page is integral to the tale being told. This narrator becomes a persona” (6). You might ask: which self is speaking and what do readers need to know about that self to trust the narrative?

Things take the time they take! While there’s joy and satisfaction to finishing, and sometimes we need to push ourselves to get there, much of the pleasure of writing is simply being in the work, making and solving problems that test our capacities and deepen our skills. Whatever your timeline or relationship to publication may be, the value and pleasure of making art are available to you.

Let’s Help a Writer

To support this book, I figured a great place to start would be the Vancouver Public Library “Suggest a Title” Form, especially since the library has a stated commitment to titles related to local history/local interest.

If you hear about a book you’d like to read and find your library doesn’t currently carry it, why not take five minutes to request it? Good for you, good for the library, good for the writer, and good for other readers who might discover it!

More Interviews on Creative Nonfiction Books

Warm best,

Bronwen

PS: If you liked this post, please hit the heart to let me know! You can also support this newsletter by subscribing, sharing, or commenting.

Introduction to Writing Poetry with 229 students.

Lois mentions the realization that “as a reliable narrator, I needed to be more forthcoming about who I was. Constructing a narrative persona is essential work for any creative nonfiction project. You might ask: which self is speaking and what do readers need to know about that self to trust the narrative?"

I just wrote the above lines in my journal as they really struck me ... is this self (to be revealed) a concrete thing, like an "identifier" ("I am X,Y,Z, I come from...") or something more abstract or made meaningful by the narrator? I'm thinking this all the time in my CNF writing... and always curious to know if I am "doing enough" for the reader.

Just a super great question to ponder, thanks Bronwen! And the baby picture of you and your mom is just delightful!

Amazing! What an incredible project and journey to writing and sharing it. And always delighted by the baby B. pics along the way!!