Kate Schapira Wanted to Write Deep and Straight and Fast Like a Tidal Channel

Writing = Making and Solving Problems, Try This at Home, Let's Help a Writer for Free!

Hi Friends,

I’m back in Vancouver and resuming my summer schedule protocols. These include things like:

Start each workday with one hour of non-goal-driven generative writing or just existing without inputs.1

While eating lunch, reading ok, but not computer open.

Anything can be canceled or reduced for body-mind care with no guilt or concern.

Does anyone else make protocols to help you inhabit times of reduced work differently?

I also have something new to share with you!

Writing = Making and Solving Problems

Over time, I’ve come to realize that problems aren’t an impediment to writing. Problems are the substance of writing: we set problems for ourselves and we work them out. In this (new! more in the works!) feature, I ask writers to dig into a specific writing problem and how they resolved it.

To start this series, I got in touch with my friend Kate Schapira, whose new book Lessons from the Climate Anxiety Counseling Booth: How to Live with Care and Purpose in an Endangered World came out in April.

I know Kate from my way back in MFA. Here’s a photo from 2005 where we’re goofing off on a window ledge after a reading. Kate’s head is just above my head (below the beautiful antics of our beloved Tod, Lynn, and Caroline). Kate and I spent hours knitting, drinking tea, and talking about writing and teaching and family and how to live (and occasionally looking up cute cats on Petfinder) together. For the past twenty years, I’ve valued Kate as the friend who will pause me in the middle of a rant to say “But why do you have to do that? Do you really have to do it?” She’s a person who questions everything, who takes nothing for granted.

For the past ten years, Kate has set up Peanuts-inspired booths in town squares, farmers markets, and bus stops with a sign reading “Climate Anxiety Counseling, Here to Listen.” Drawing on over 1200 booth conversations, she wrote this book. “I began to hear how complex our reactions to climate change are,” she writes, “and how our efforts to protect ourselves from the worst feelings get in the way of protecting each other from the worst consequences” (xi). The book unites information and stories with questions and practices, inviting reflection and concrete action.

Here’s my conversation with Kate!

What are three key things to know about this book?

It is full of models and methods for doing what the subtitle says: living with care and purpose in an endangered world. More specifically, it has practices and questions for using our emotional responses to climate realities as a guide to community connection and collective action.

If you can read it and talk about it and do the exercises in it with people, you will have a richer and more interesting and more pleasurable time.

I tried to worry less about whether it was despairing or hopeful and think more about how it could be put into practice.

What’s a problem—small or large—that you encountered while making this book? What did you do? How did you move forward?

One major problem was voice. My first six books were books of poems, specifically poems in a mode where being directly communicative was not the priority. As you know, since we did it together, I came through an MFA program with a focus on what could happen around the edges of language, and how you could be playful, challenge expectations, maybe sneak up on meaning or feeling, create an atmosphere to inhabit or an experience for people to have. One of the very first things I knew about this book—even before I totally knew that I wanted it to be a book or what form I wanted it to take—was that I didn't want it to be like that. I wanted it to be communicative in a strong and straight-flowing way.

I had this image of a tidal channel at the mouth of a little river in Southern Rhode Island called the Pettaquamscutt. The water flows deep, straight, and fast through that channel. It's also full of little creatures. That was the image I held in my head when I started to make this book.

But I absolutely cannot stress enough how out of practice I was with writing like that!

I had a tremendous amount of help at every stage of the process. Two long-time writing friends—we’ve been sharing writing and commenting on each other's work for over 10 years—read every chapter. An interviewee in the book who became a friend through the process also gave a lot of feedback like, “How will people understand this? What will make this available to people?”

Then I had incredible support at the proposal stage from my agent Jen Marshall and my equally incredible editor Renee Sedliar at Hachette. They’d say, “You know, you have to say it. You can’t talk around it. You have to actually say it” or “Do you know what it is that you are trying to say?” Sometimes, I had to be like, “Shit, Kate, stop lyrically evoking!” I didn't realize how much poetry was allowing me to cover my own emotional ass when I was writing. I had to walk that back and then walk off in a different direction I was not practiced in.

I had this image of a tidal channel at the mouth of a little river in Southern Rhode Island called the Pettaquamscutt. The water flows deep, straight, and fast through that channel. It's also full of little creatures. That was the image I held in my head when I started to make this book.

I also grappled with how to make the book available to people in another sense. The book is full of exercises and it’s quite prescriptive, like, "Hey, I think you should try this. I think it'll be better for the climate and for you if you try this." I took so many steps to make sure those recommendations were not rooted in narrow assumptions about the people who read the book. I needed the book to be usable by people who are not like me, which is most people. Most people aren’t like me and they mostly aren’t like each other!

Again, this was a challenge I feel I’ve mostly surmounted by listening to other people. An example: early on, I did one of the exercises with a small group of friends I’d been meeting with for ritual and ceremony. After the exercise, someone said, “Kate, the form of this question implies that we haven’t yet experienced a great loss. But you can’t assume that. That’s not true for most people.” So that was an early instance of the kind of alertness and check that I drew on from the people around me.

Here’s a later example: I ran an independent study at Brown where a group of students tested the book out and did writing based on some of the exercises, and made connections to other climate or organizing work they were doing. One of the exercises in its original form asked people to envision “the climate impact that they were most afraid of.” When we did a debrief, a student said, “Do you have to say most? Cause if you say most, then people get stuck trying to compare in their heads, but if you just ask for an impact, then they’ll go with the first thing that comes to mind.” It felt so clear to me. Yes, I want people to focus on what is present for them in that moment. The book was almost done, but I went through it and took out every superlative.

For both of these problems, I was able to move forward by having so many alert people paying attention throughout the process.

Kate Schapira has been listening to people about climate change for ten years, at the Climate Anxiety Counseling booth and elsewhere. She lives in Providence, Rhode Island, where she teaches nonfiction writing at Brown University and is involved with local efforts toward environmental justice, climate justice and peer mental health support. Lessons from the Climate Anxiety Counseling Booth: How to Live With Care and Purpose in an Endangered World is her first full-length work of nonfiction; she’s also written six books of poems. Her prose has appeared in Catapult, The Rumpus, The Toast, and as a chapbook from Essay Press called Time to Be Something Other Than Human. You can subscribe to her newsletter and find her on Instagram. She never met a tidepool she didn’t like.

Try This at Home

Picturing a “deep, straight, fast” channel of water helped Kate embrace directly communicative—even prescriptive—writing after years of composing poetry. A powerful image can offer a center, a compass for navigating all of the problems and choices we face as writers. What image comes to mind when you think of your current project? What image comes to mind when you imagine how you want this project to reach people?

Kate’s main writing solution, like the key message of her book itself, relies on the power of community. When and how do you share your writing with others? Whose insights do you seek out? How do you nurture relationships of trust and reciprocity to support your work over the long haul?

Let’s Help a Writer for Free

There are many ways to help a book find its people that don’t cost money. One great way is to use your local libraries!

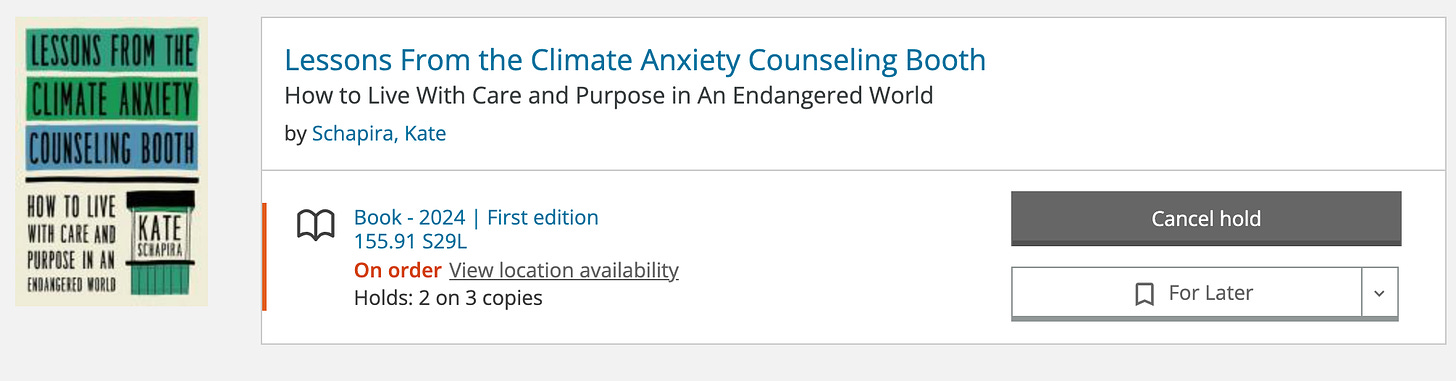

First, I looked up Kate’s book at Vancouver Public Library (VPL or vupul as my kids call it). It looks like three copies of Kate’s book are on order! Even though I already bought the book, I placed a hold to send a message to the library that people are interested in this book (and they might want to get more copies).

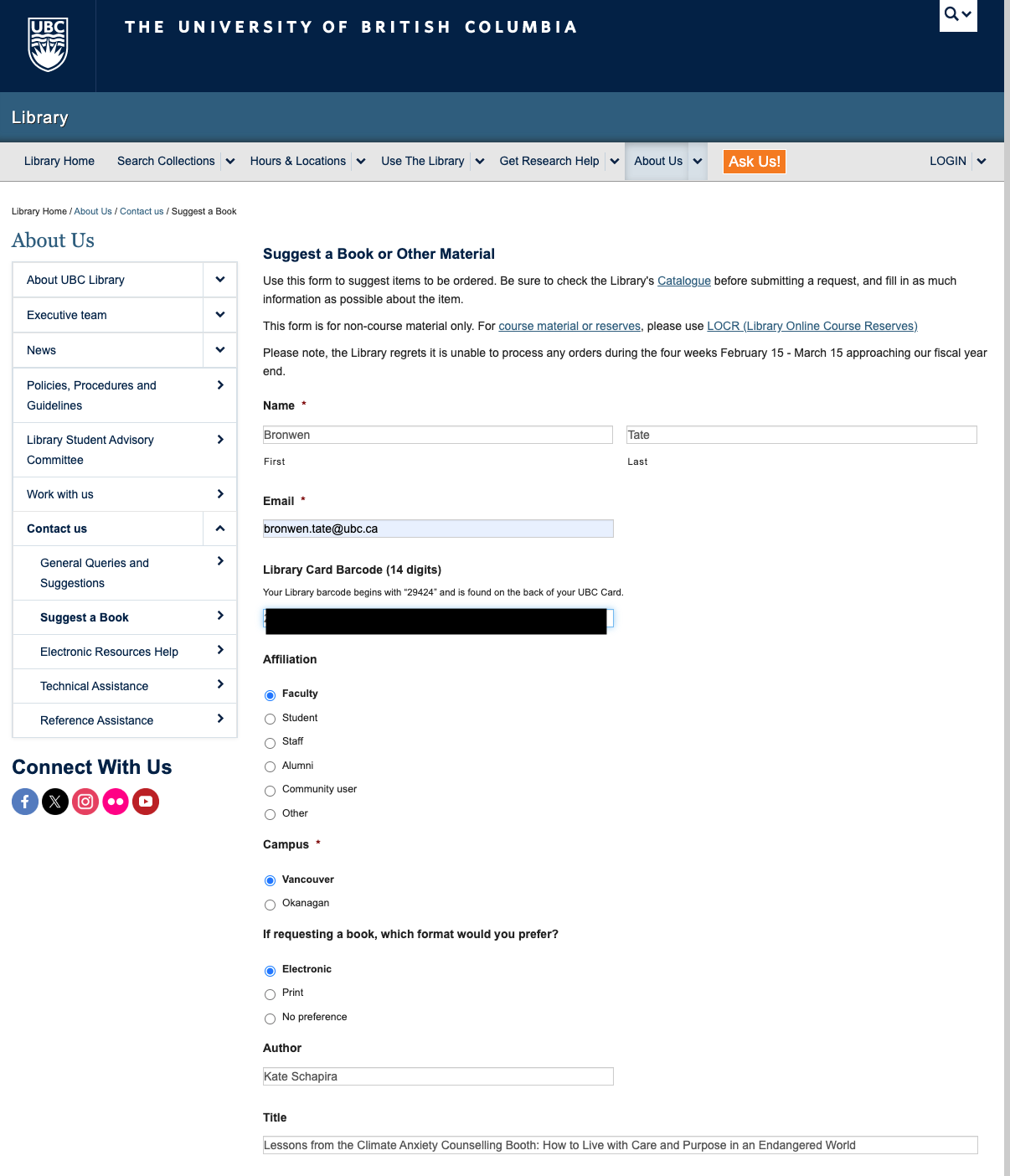

Then I checked my institutional library at the University of British Columbia. I didn’t see any record of Kate’s book, so I filled out a form to suggest the book (I couldn’t find the form in a menu right away, but Googling “UBC recommend a book” turned it up). I got an email the next day confirming that the book had been ordered!

Join me! Support a writer by placing a hold or suggesting a book (Kate’s Lessons from the Climate Anxiety Counseling Booth or any other book you’re curious about or eager to support) at your local public and/or institutional library. Then let me know in the comments so I can cheer you on!

Warm best,

Bronwen

PS: If you liked this post, please hit the heart to let me know! You can also support this newsletter by subscribing, sharing, or commenting.

I keep a list of options stuck to a corkboard that includes things like “make tea” or “stare out window” alongside “syntax études,” “typewriter poems,” and “freewriting from a keyword.”

Hi Bronwen, I really enjoyed this feature on Kate's book (she was also in Catherine Imbriglio's Lyricism & Lucidity class that I took my senior year) and I requested her book at my local library. I've been enjoying your newsletters and hope you're doing well!

And here the book is for anyone at UBC: https://webcat.library.ubc.ca/vwebv/holdingsInfo?searchId=25552&recCount=100&recPointer=0&bibId=13332900 — it's an EPUB e-book available for full download. :)