Hari Alluri Reconnected with the Source Code

Writing = Making and Solving Problems, Try This at Home

Hi Friends,

Writing = Making and Solving Problems

Over time, I’ve come to realize that problems aren’t an impediment to writing. Problems are the substance of writing: we set problems for ourselves and we work them out. In this feature, I ask writers to dig into a specific writing problem and how they resolved it.

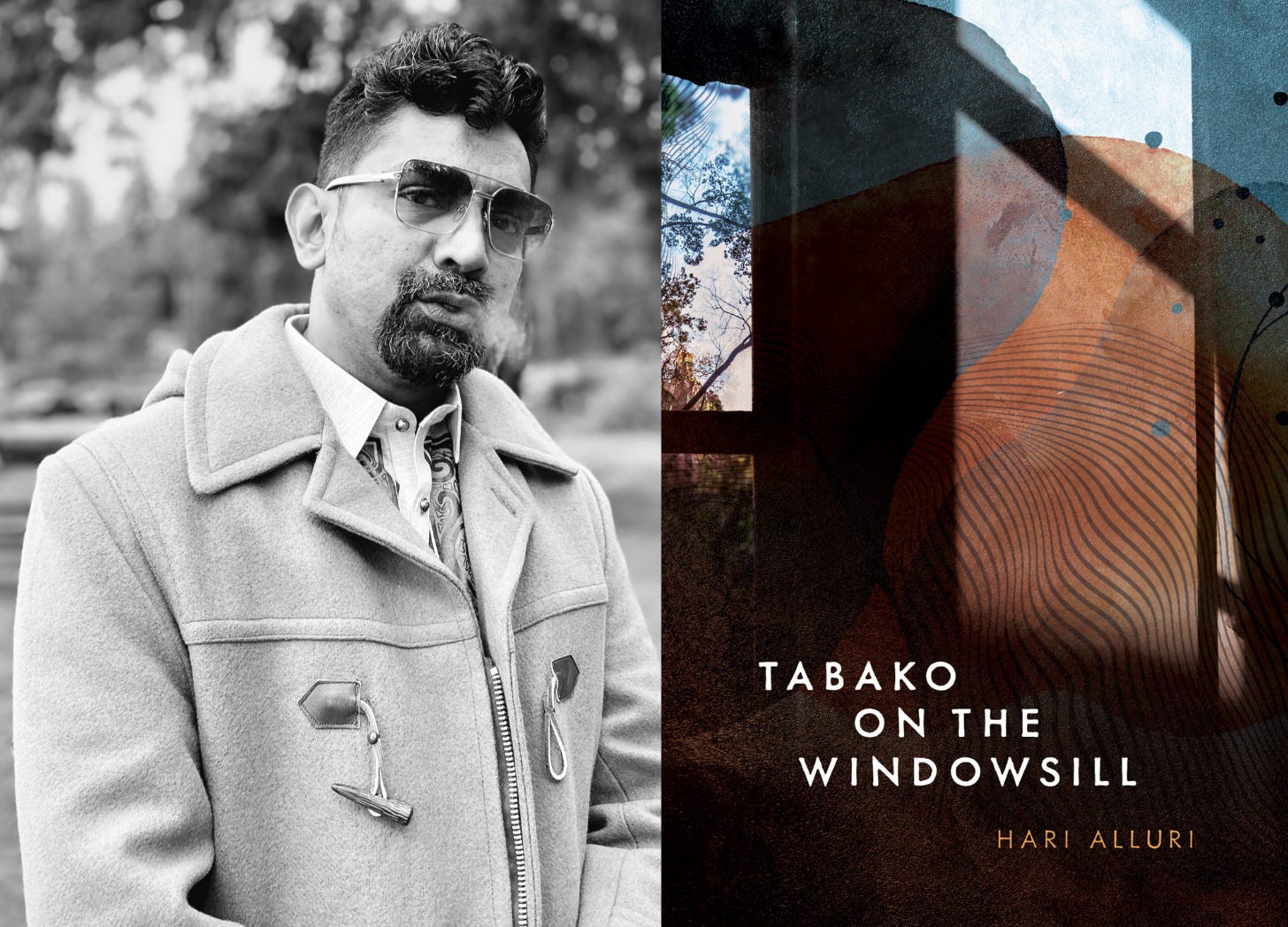

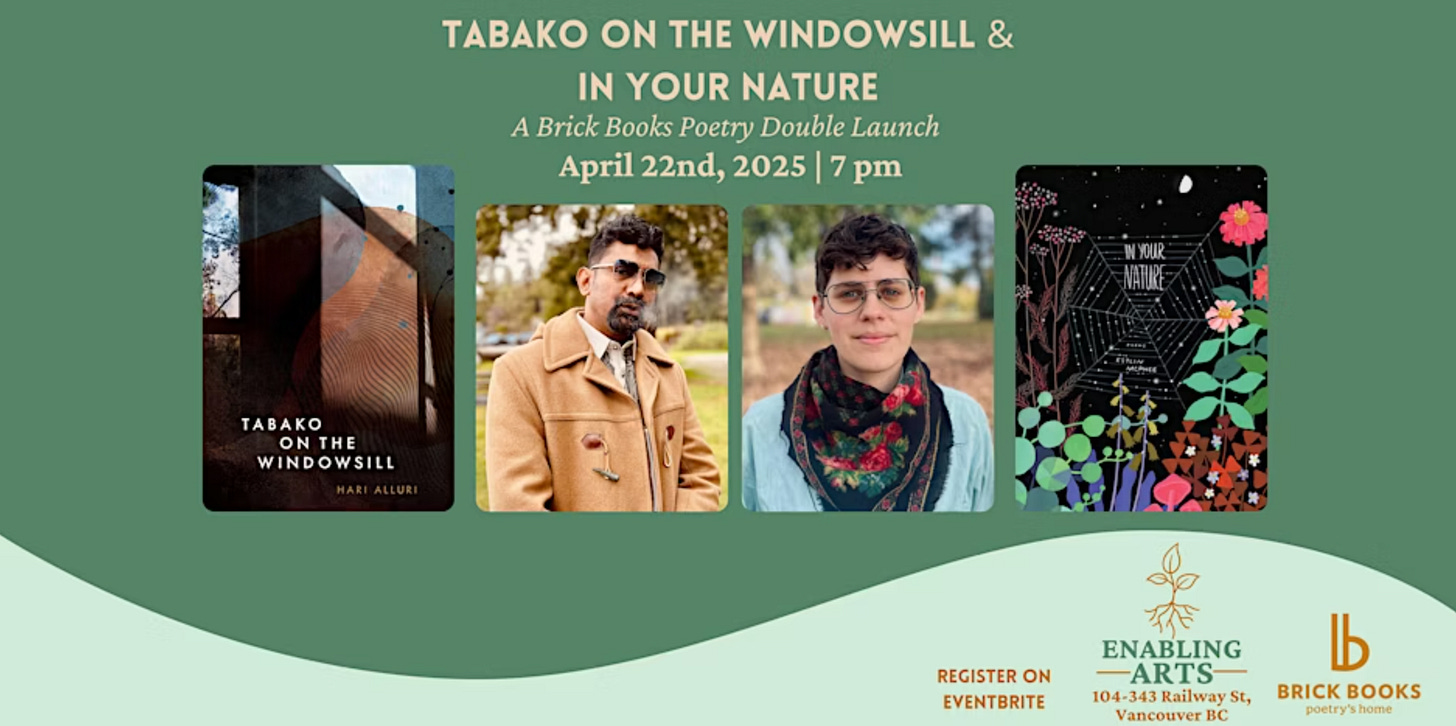

I met Hari Alluri at a Dead Poets Reading Series event where he read José Garcia Villa (who I’d read in grad school and who does wild things with commas, which we enjoyed discussing!). Later, we read together with Kazim Ali and friends (we were part of the “and friends”) and got to eat and talk poems after. I’d taken the bus to the reading, and at the end of the evening, Hari drove me and another writer home, going considerably out of his way. I’m pretty sure I saw something fundamental about who Hari Alluri is in the world that evening: the friend who drives you all the way home. I spoke with Hari about his new book Takabo On the Windowsill, published last month by Brick Books (and launching in Vancouver tomorrow April 22nd, see below!), and so many moments from our conversation have been on my mind ever since. I’m so pleased to share this conversation with you.

What are three key things to know about this book?

All myth, as Chris Abani says, is meant as an initiation into a process that transforms you. One such practice is offerings, and Tabako on the Windowsill is a book with literal offerings in it. Several poems are titled "Poem to Burn," and I give thanks to Kilby Smith-McGregor, who designed these poems with a little scissor picture and a dotted line to cut along and nothing on the other side of the page. When I lead workshops, I often end with an offering. We each write down something we want to release or something we want to call in, and then we burn them. This is an homage to that practice, which I know to be ancient.

Shout-out to Sherwin Bitsui, who speaks about shadow architecture. One of my shadow architectures is the spiral. In my first two books, it was the spiral of the long-distance phone call, the landline, that long curve of wire. And for this book, it’s the spiral of smoke and the relationship between offering and response.

I came to poetry through community organizing, and I’ve always wanted to displace self. When your singular identity is multiplicitous, self is already displaced. I wrote these poems to folks in the world I live with and ones I’ve lost. In this book, I work deeply with Anagolay, Tagalog goddess of lost things. Doing so taught me about surrender and retrieval—she reminds us that in doing so you never fully lose anybody. If you carry them, then they can never be lost. What does it mean to carry the privilege of holding a single devastating loss when so many folks in Palestine, Congo, Sudan, all around the world, do not get to hold their losses in the single individual ways that each one deserves? It felt important to express that privilege in the fullest way that I could, to make these poems of address as an example of the intimacy I hope for everybody. On the flip side, these poems are to beloveds I owe so much to, community I walk with, my godkids and my nieces, who are the living embodiment that loss isn't the only thing. The book is also for them.

What’s a problem—small or large—that you encountered while making this book?

In all three of my major projects, there's been a single poem I was trying to write that carried more than a single poem could hold, and these poems became the source code for each book. The Flayed City is really a single poem with interruptions, though a different one than the one I initially tried to write. For this book, it was a poem with a lot of repetition, a litany of history, myth, family, loss, a poem thinking about borders and displacement. It was trying to be the litany that the individual offerings of this book ultimately became.

More recently, though, I thought the core structure of the book was a group of poems I was writing in response to Avatar the Last Airbender (the animated series, which I love). I started with a core response to Hama called “Hama, at Cavern’s Mouth.” But then I realized I had other poems that had already crossed the bridge into being. They had gravity already, whereas the Avatar poems were still ideas. There was potential in that material, but I felt the actual in this material. These poems had reached horizons of becoming that didn’t require an attachment to me: I no longer needed to be in direct contact with them for them to exist. But then what happens when you take out what seems to be the center of the work?

What did you do? How did you move forward?

This phrase "give thanks" kept showing up multiple times throughout the draft, and Chris Abani reminded me that when you give thanks, you're acting in response to a fear, traditionally. I thought about giving thanks and about making offerings. If I give thanks for waking up, I'm giving thanks for not having died in the night. If I give thanks for my food, I'm aware that hunger is possible. It's an awareness of fear, of the possibility of things being taken from us or of not having access to these things in the first place. It becomes a reminder of all that we can lose.

The moment that focus was unlocked, I must have written nine poems in nine days or something ridiculous like that. I went back to material from even before the beginnings of this project, and it was like, oh, there’s the source code right there. It’s been waiting for me for years in work I thought wasn’t even part of this project.

I think of poems as beings that have their own work to do. Poems think in specific ways and have desires in specific ways. Each form—be it a received form or a traditional form or an innovative form—has intrinsic desires and ways of seeing the world. I’ve worked outdoors quite a bit in my lifetime, and if you walk around with a rake, you will find things to rake up. If you have a sonnet, you’ll find things to sonnet. The sonnet has specific desires based on the way it unfolds, the importance of the volta—whether it's an extension or a complication—and the possibility the final moment opens towards. There are two ghazals in the book because that's the way grief works. Lamentation is this repeated thing that is impossible to let go of and necessarily different each time it arrives. It doesn’t unfold in a narrative form. It requires returning, requires fragmentation.

I've always had long arms as a poet; it's my own multiplicity. This can be a difficult thing—many conventions of writing resist multiplicity, and notions of authenticity are often singular notions. They crystallize and atomize separate instances of authenticity, make us legible through reduced identities or reduced roles under capitalism that we do or don't carry out. To carry the fully multiple into a poem is always to risk illegibility. Honoring that is what distinguishes actual work from potential work. A poem can be (and I hope these poems are) clear in and of themselves and still not seem easily legible. More important than a poem’s legibility is its embodiment. And if it can carry that embodiment beyond legibility, then you give thanks. The poem becomes an offering that can go out into the world and do its work.

Hari Alluri (he/him/siya) is an award-winning migrant poet, performer, editor, and facilitator who connects to the world, gratefully, on unceded Coast Salish territories of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh peoples, and unceded land of the T’uubaa-asatx Nation. Author of The Flayed City (Kaya Press) and chapbook Our Echo of Sudden Mercy (Next Page Press), his new collection is Tabako on the Windowsill (Brick Books). With work available widely in anthologies, journals and online—including Best of the Net, Contemporary Verse 2, Library of Elemental Bending Vol. 1 (SMALL CAPS / TCR), Poem-a-Day, Poetry, and We the Gathered Heat anthology (Haymarket Books)—his recent collaborations include Burnaby Art Gallery, The Capilano Review’s Emerging Writers’ Mentorship Program, Centre A, Community Building Art Works, The Digital Sala, Filipino Canadian Book Festival, Indian Summer Festival, Liars of Orpheus, Vancouver Poetry House, and many more.

@harialluri | https://linktr.ee/harialluri

Try This at Home

Hari talks about moments when he realized that a poem “carried more than a single poem could hold” and how these poems “became the source code” for each of his books. Do you have a poem (or a paragraph) that’s holding so much that it’s spilling out at the seams? What might it mean to think of this material as “source code" and let it expand? Try placing lines (or phrases or sentences) on their own pages and using them as starting points for freewriting.

“If you walk around with a rake, you will find things to rake up,” Hari said, explaining how poetic forms like the sonnet or the ghazal each have “intrinsic desires and ways of seeing the world.” If you’re someone who tends to work with form emergently, discovering a poem’s shape over time through revision, you might try out a practice of carrying a form (sonnet (I’ve done this), ghazal, duplex, Lorine Niedecker’s five-line riff on the haiku (I’ve done this too)) around for a period (say, a month of daily practice?) to see what you find to “rake up.”

Hari and I talked about how “conventions of writing resist multiplicity, and notions of authenticity are often singular notions.” Try returning to a draft with a goal of faithfulness to the fullness of your own multiciplicity. What happens when you refuse to reduce, oversimplity, or perform singular legibility?

Vancouver + Portland Events

Vancouver friends, join me at Hari Alluri and Estlin McPhee’s book launch (with Marc Perez and Raoul Fernandes) at Enabling Arts TOMORROW April 22nd at 7 pm.

I’m also very much looking forward to reading (and listening, eating cake, dancing, and possibly reading your tarot) at A.E. Osworth’s Vancouver book launch May 4th at Slice of Life Art Gallery. Read my conversation with Osworth about writing this book:

Portland friends, I’ll also be in the audience for Osworth’s May 1st event at Powell’s Books on Hawthorne, which happens to align with a trip to care for my dad (who is doing really well post-transplant—thanks for your warm wishes!).

More Like This

Warm best,

Bronwen

PS: If you liked this post, please hit the heart to let me know! You can also support this newsletter by subscribing, sharing, or commenting.

WILD THINGS WITH COMMAS!!!!

"Source code" -- I love that!

Fellow Canadian writer Karen Connelly wrote a series of books loosely about the same subject: her time in Thailand. First she wrote poetry. Then she wrote a non-fiction book. Finally, she wrote a novel, "The Lizard Cage".

That fascinated me when she talked about it during one of her workshops. Although neither she or I used the term "source code", that's exactly what it is. Or, rather, that's exactly how I interpret her progression of work -- I'm not speaking for her.

I adapted her approach to create EFFing (Emotion, Fact, Fiction) Writing to help me start with the emotion. Expressing emotion is definitely one of my weak spots (writing or otherwise), so I wanted to help myself inject more of it into my novel.

It's still a work in progress (the approach AND the novel), but I'm very happy with the results so far.

I wrote about it a while back on my own Substack platform, if you're interested: https://www.towritewithwildabandon.com/p/how-to-start-effing-writing

I know that this is a bit of a tangent, but I figured there were enough parallels that's I'd pipe up!

Break a pen, both of you, at your upcoming readings!